In our journey through life, we often focus on external appearances, material possessions, and societal achievements. Yet, the true essence of who we are resides within our soul or spirit. Everything else, from our body to our clothes, fame, and reputation, are merely layers of clothing that adorn our core self. By understanding this perspective, we can better appreciate the significance of nurturing our inner self to achieve true harmony and fulfillment.

The Soul: Our True Self

At the heart of our being is the soul, our true essence. This innermost core defines who we are beyond the physical and material aspects of life. It is the source of our values, beliefs, and purpose. When we connect with our soul, we align ourselves with our deepest truths, leading to a more authentic and meaningful existence.

The Body: Our Most Precious Clothing

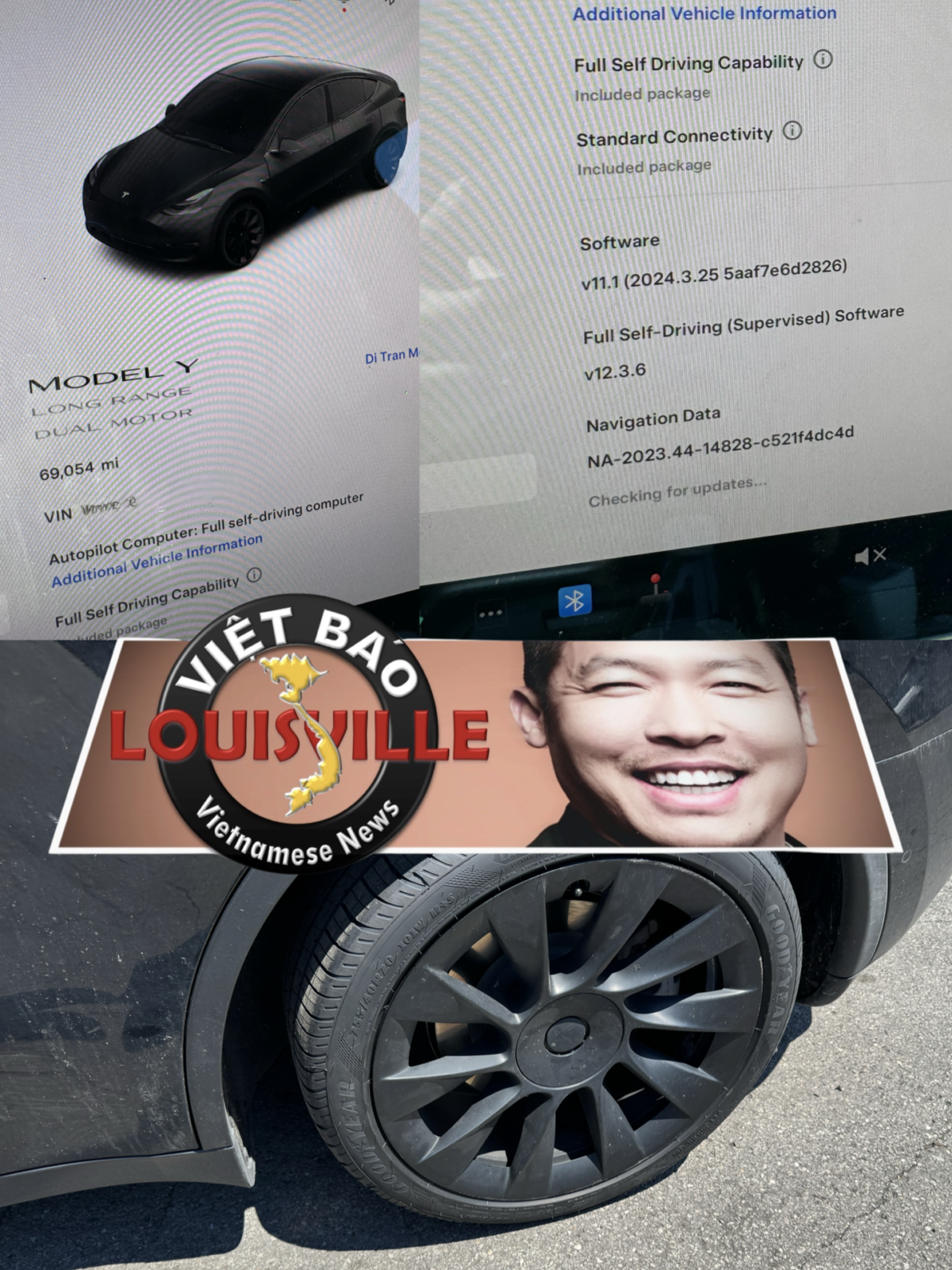

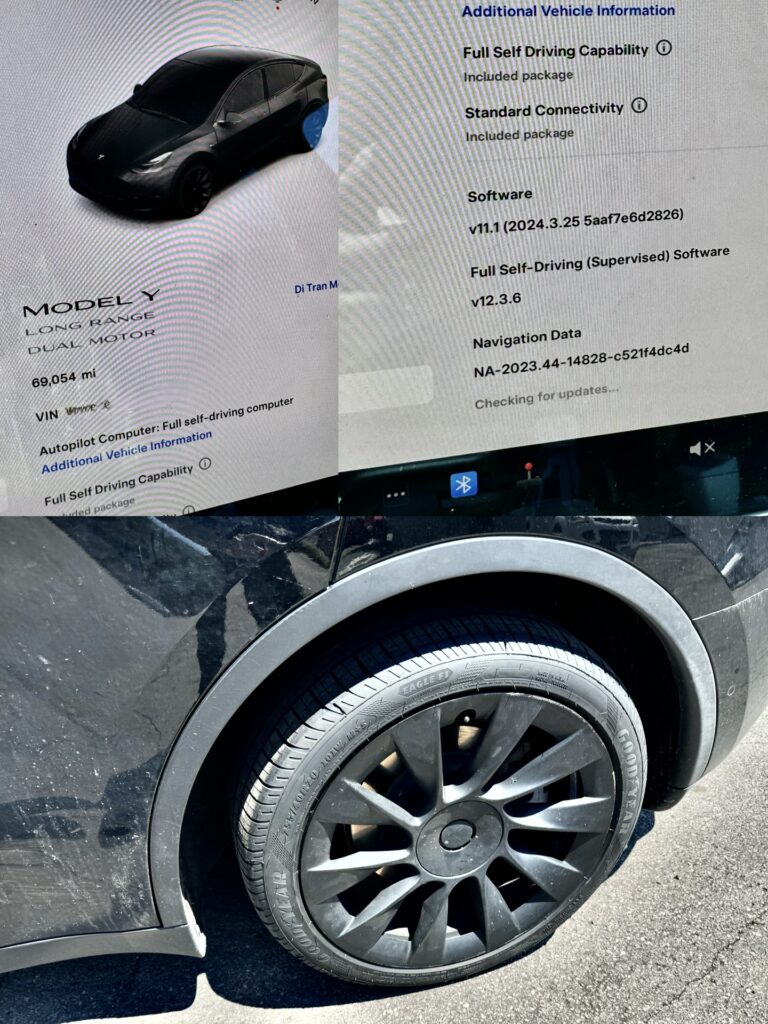

The body, often considered our physical identity, is the first layer of clothing that presents our soul to the world. It is the most intricate and custom-made attire we will ever possess. Unlike material clothes, which can be bought or changed at will, our body is unique and irreplaceable. How we care for and present our body reflects our inner state and self-respect.

To truly represent our inner self, we must take care of our body. This involves maintaining physical health through proper nutrition, exercise, and rest. It also means embracing our body’s uniqueness and understanding that our physical appearance is a direct reflection of our inner well-being.

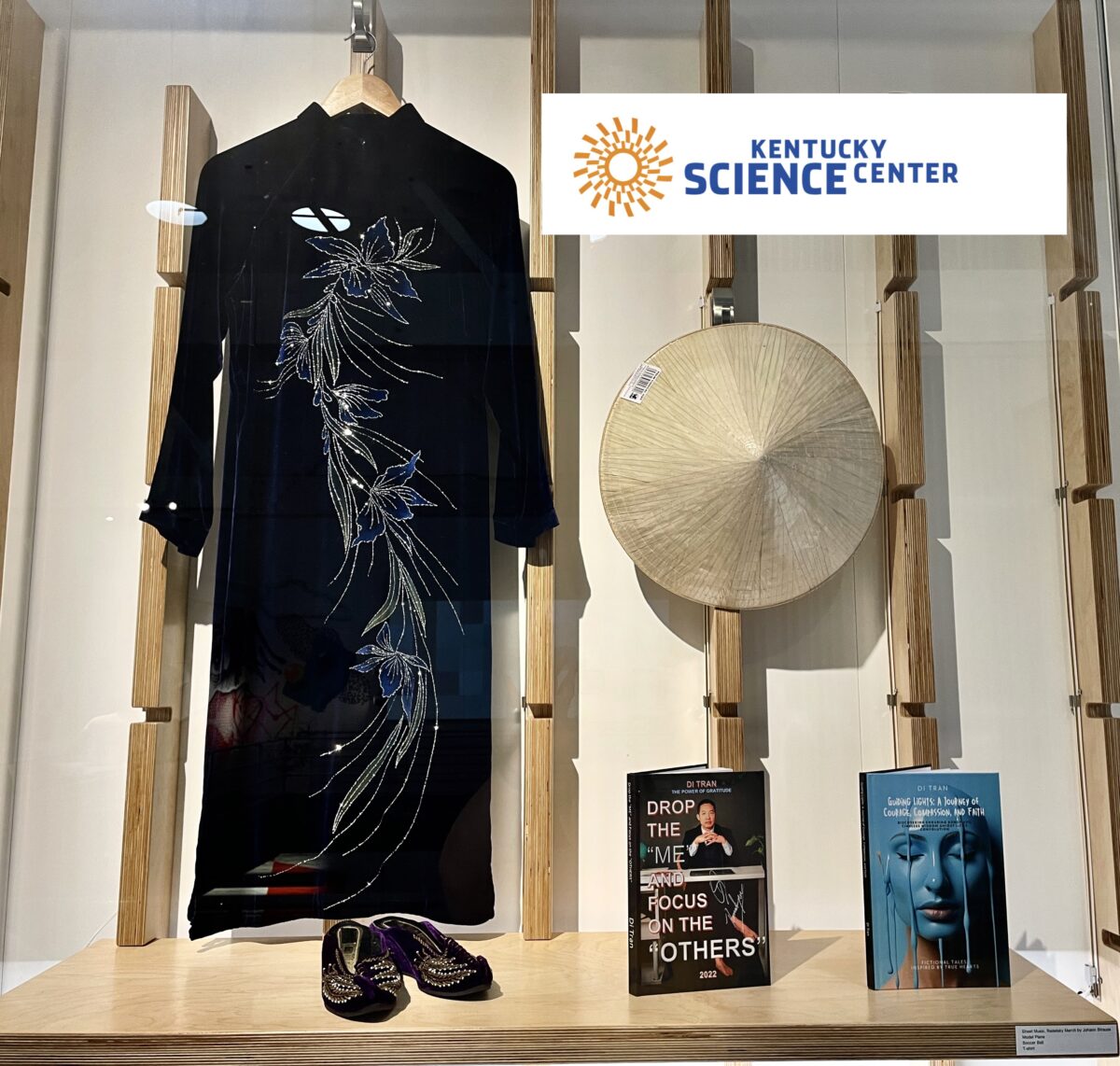

Clothes: External Decoration

Clothes are the third layer, an external decoration that enhances our physical presence. They are expressions of our personality, mood, and social status. While important, clothes are transient and superficial compared to the body and soul. They can be changed easily, yet they still play a significant role in how we present ourselves to the world.

Fashion and style can be powerful tools for self-expression, but they should not overshadow the importance of the layers beneath. True confidence and beauty emanate from a well-nurtured soul and a healthy body.

Fame and Reputation: The Outer Projection

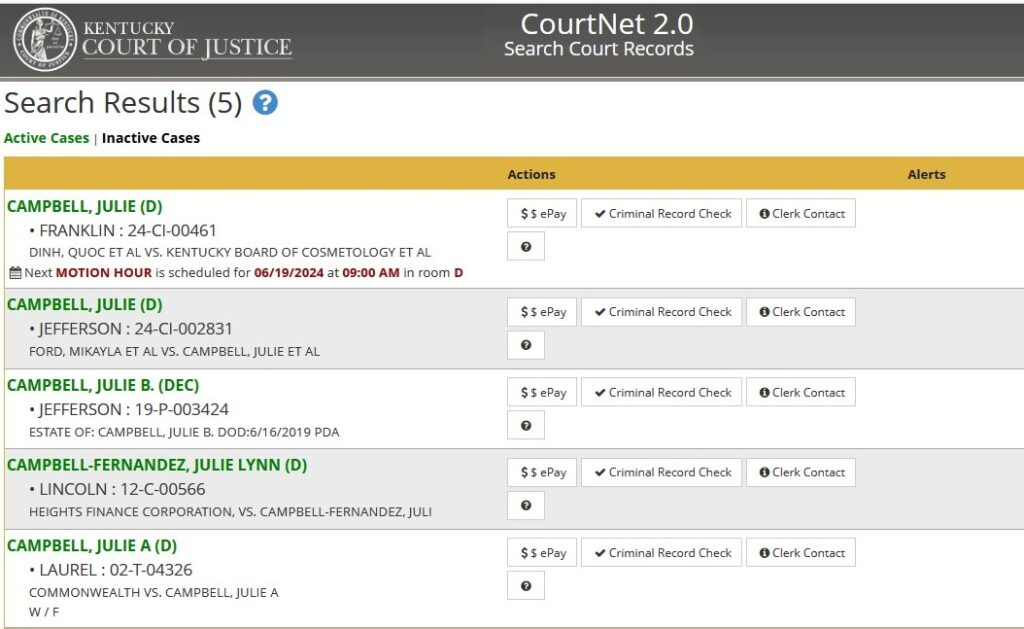

Fame, reputation, and social standing are the outermost layers of our ‘clothing.’ They represent how others perceive us and the impact we have on the world. While these aspects can influence our opportunities and interactions, they are ultimately reflections of our inner and physical layers.

To cultivate a positive and enduring reputation, we must first focus on our inner development. Authenticity, integrity, and kindness originate from within and naturally project outward, shaping how we are perceived by others.

Customizing Our Inner Attire

The process of customizing our body to best represent our soul starts from within. By tuning into our inner self, we can align our actions, habits, and lifestyle with our core values. Here are some steps to achieve this alignment:

- Self-Reflection: Regularly reflect on your values, beliefs, and goals. Understand what truly matters to you and how you want to express it in your life.

- Healthy Habits: Adopt habits that support your physical health and well-being. This includes balanced nutrition, regular exercise, and sufficient rest.

- Mindfulness: Practice mindfulness to stay connected with your inner self. Meditation, journaling, or quiet contemplation can help you maintain this connection.

- Authentic Expression: Use fashion and style as tools for self-expression, but let them reflect your inner self rather than conforming to external expectations.

- Positive Actions: Act with integrity and kindness. Let your actions be guided by your inner values, contributing positively to your reputation and impact on others.

By focusing on our inner development, we can ensure that each layer of our ‘clothing’ – from our body to our outward appearance – authentically represents our true self. This holistic approach leads to a harmonious and fulfilling life, where inner and outer selves are in perfect alignment.

In essence, the journey to true self-representation begins within. By nurturing our soul, caring for our body, and expressing ourselves authentically, we create a powerful and genuine presence that resonates with others and the world around us. So, tune from within, and let your true essence shine through every layer of your being.