In the heart of Louisville, an extraordinary event unfolded at the majestic Cathedral of Assumption: Let’s Dance Louisville for FEED MY NEIGHBOR. This night brought together a remarkable tapestry of individuals, each contributing to the beauty and unity of our city. Among them, the spotlight shone brightly on Morgan Hancock and her dance partner, Jani Szukk, whose story exemplifies the essence of hard work, resilience, and community spirit.

Morgan Hancock, an Army veteran and devoted mother, is a beacon of strength and determination. Known for her relentless hustle in the business world and her leadership in community-serving initiatives like Bourbon with Heart, Morgan’s dedication to serving others is truly inspiring. Her performance at Let’s Dance Louisville was more than just a dance; it was a testament to her unwavering commitment to making a difference.

Dancing alongside Morgan was Jani Szukk, a professional dancer from Hungary who recently became a naturalized US citizen after years in America. Their performance, themed “American Proud,” beautifully embodied the spirit of patriotism and the joy of achieving the American dream. Jani’s journey from immigrant to citizen resonates deeply, especially with those who, like him, have come to this country seeking a better life.

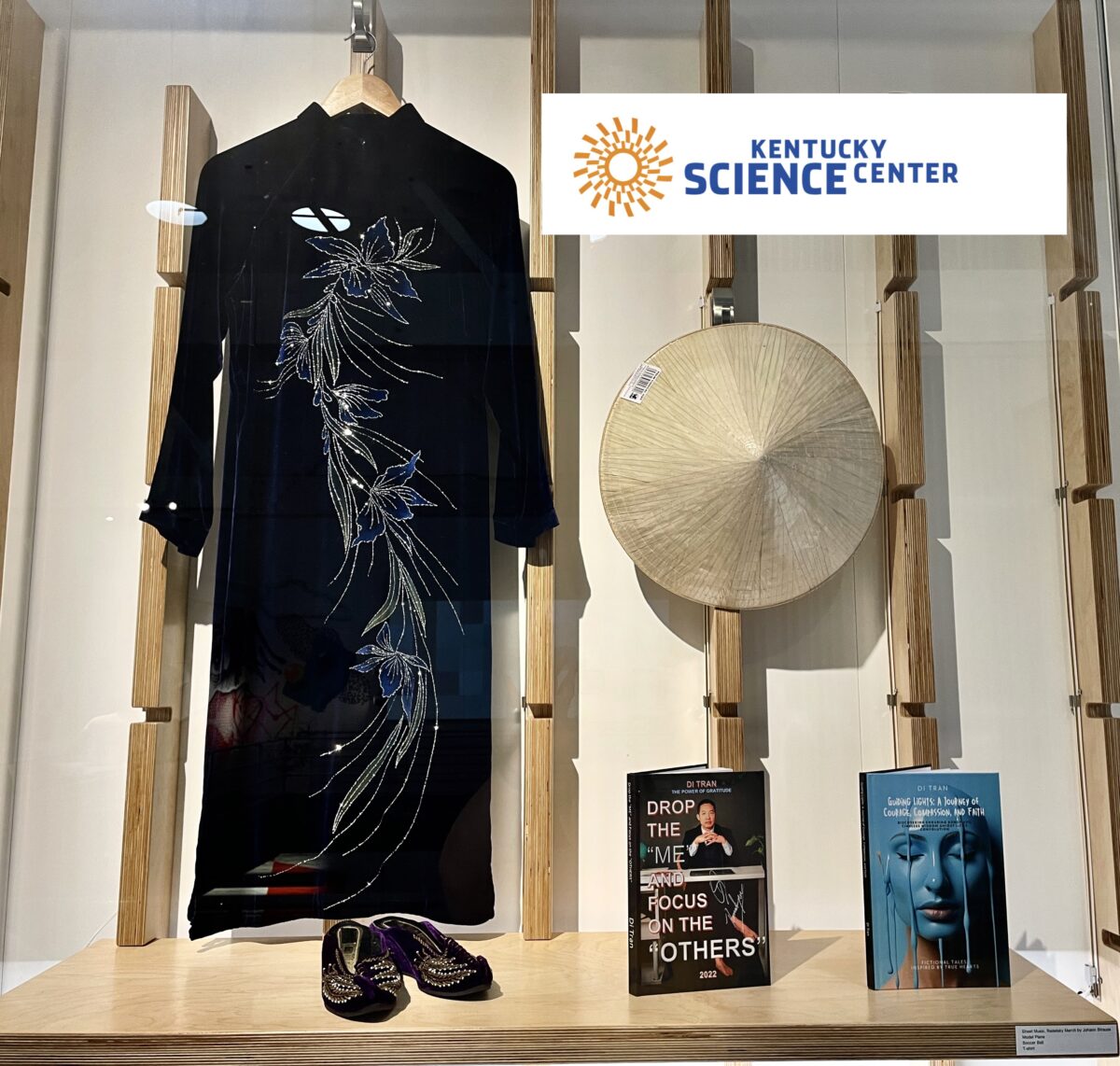

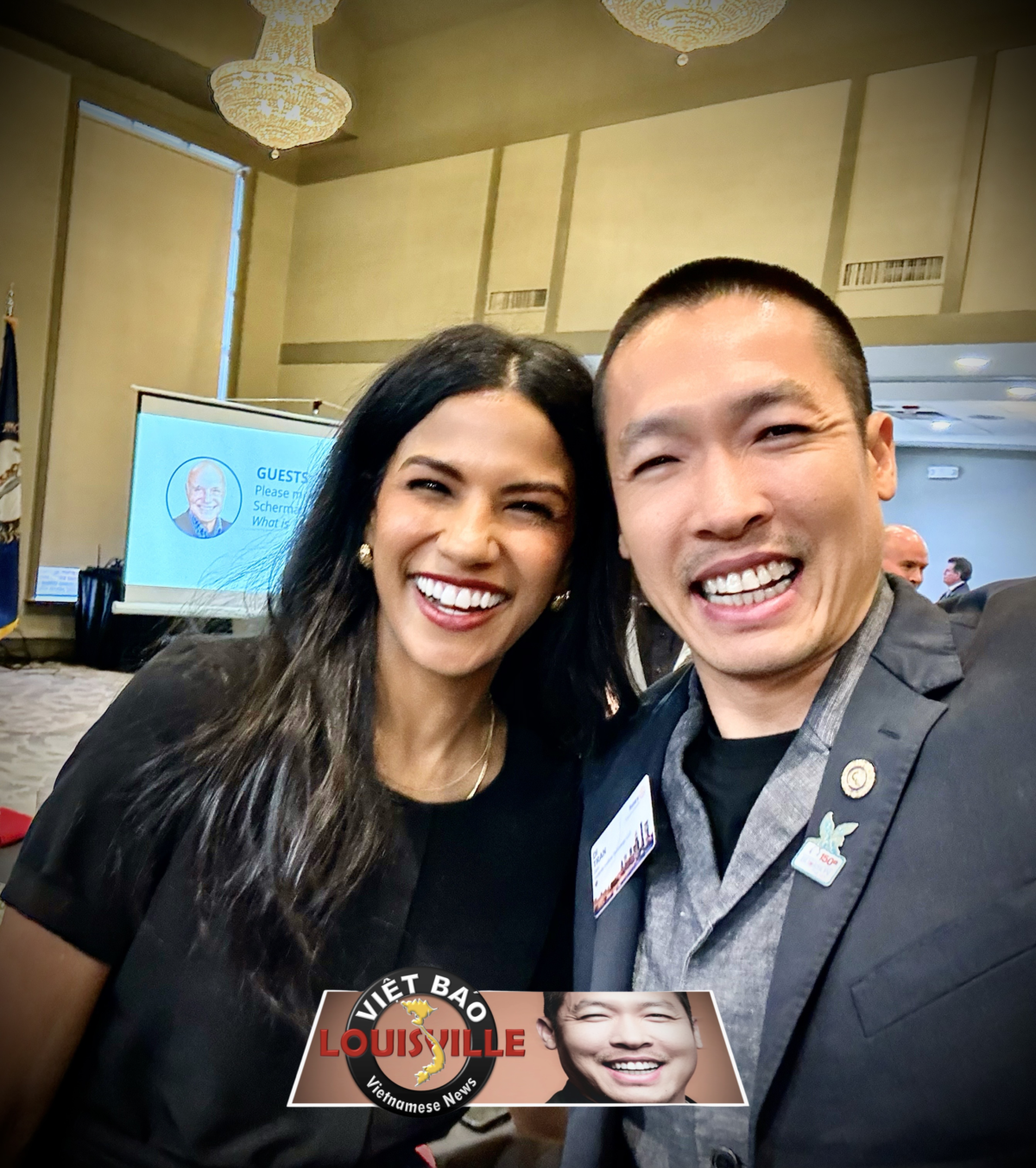

The event also saw the presence of Vy Truong, the Founder, CEO, and licensed Pharmacist in charge of Kentucky Pharmacy. Vy’s story is one of perseverance and excellence. As an immigrant and successful business owner, she exemplifies the profound impact that dedication and hard work can have. Alongside Vy was her husband, Di Tran, a Vietnamese immigrant, serial small business owner, and author of a series of self-help books. Di is known for his tireless efforts in serving the community and raising his three sons with the values of hard work and compassion.

The synergy among Morgan, Jani, Vy, and Di highlights a powerful narrative of unity and service. These individuals, each from different walks of life, are united by their shared commitment to bettering the community. They demonstrate that the beauty of our city lies not just in its landmarks but in the hearts of those who strive to make it a better place.

This event, elevating the cause of FEED MY NEIGHBOR by the Cathedral of Assumption, underscores the incredible potential of community-driven initiatives. It is a reminder that through collective effort, we can address pressing needs and create a more compassionate society. The support and collaboration witnessed here are a testament to the power of unity and the profound impact of serving others.

In the grand tapestry of Louisville, stories like those of Morgan, Jani, Vy, and Di weave a narrative of hope, resilience, and unwavering commitment to the greater good. They exemplify the spirit of “mom bosses,” immigrants, veterans, and community leaders who tirelessly work to create a better future. Their efforts, combined with the mission of organizations like FEED MY NEIGHBOR, illuminate the path forward—a path paved with love, service, and the beauty of God’s grace.

As we reflect on this night, we are reminded of the profound truth that the beauty of our community is found in the hearts and actions of those who serve. Let us continue to support and celebrate each other, knowing that together, we can achieve extraordinary things. The journey of unity, service, and love is just beginning, and there is so much more to come.

May God bless all who contribute to this noble cause, and may the spirit of service continue to inspire us all.